It's four o'clock in the morning in a remote Ecuadorian rain forest, and the odd thing is how much, at this wee hour of the day, the forest feels like a deserted city street. The electric hum of insect life that gives a tropical rain forest its sizzle is switched off. And that, says Terry Elwin, an entomologist from the Smithsonian Institution, is why we're awake an on a forced march to his study site. We have to get there at the Insect's world equivalent of the Cinderella hour, when both the day and night roaming insects are at rest in the trees. Only during that sliver of time, Erwin had explained to me, could he and his team of students catch them all.

Silently we travel single file through the dark woods, our headlamps catching bright pools of light along a narrow, muddy trail. I see Erwin, a wiry, fit man in his late 50's, pause at a small stream ahead of me, then jump across. "It's higher today," he calls over his shoulder as he presses on. In the dark I can't judge how high the stream is so I simply step in, only to sink up to my knees. Brown water pours into my calf high rubber boots, but theres no time to empty them: We have an appointment to keep. I squish along after Erwin, listening to the cries of dismay of others behind me who meet the same wet footed fate.

A half hour later we reach a trail marked with pink surveyour' tape, and the team moves into action. Erwin and two students load two gasoline powered foggers, which look like leak blowers, with a biodegradable insecticide while other team members run down the trail, suspending ten white sheets just above the forest floor, at random intervals. When the last sheet is open, Erwin looks at his watch: It's 4:40. "Ready?" he asks his crew. They nod yes. "Then vamos a comenzar- Let's begin!"

Erwin starts up one fogger and aims it at the night sky. The roar of the motor rips through the forest while an acrid blue-white cloud rises in a narrow column above the first sheet. LAzily, the deathly cloud passes through layers of spindly braod-leaved shrubs, engulfing every leaf and twig. It swirls over the tops of lacy fronds of palms and tree fenrs and climbs up the smooth sided trunk of a giant fig tree to the tips of its branches and the stars beyond. Within seconds insects begin to spill from their resting perches onto the sheet below. But Erwin doesn't wait to see what he has caught; he's off running down the trail to the next site, where he points the fogger again at the sky.

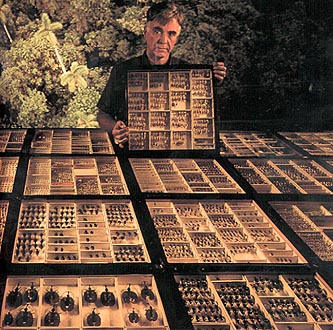

Such an inventory of the forest's insects is important, Erwin had explained earlier, as a measure of the forest's overall diversity- the shorthand term the biologists use to describe Earth's bountyful variety of life. Based on similar counts he's made, Erwin estimated that we share the Earth with some 30 million different species of animals and plants.

Taken from National Geographic Magazine, February 1999.